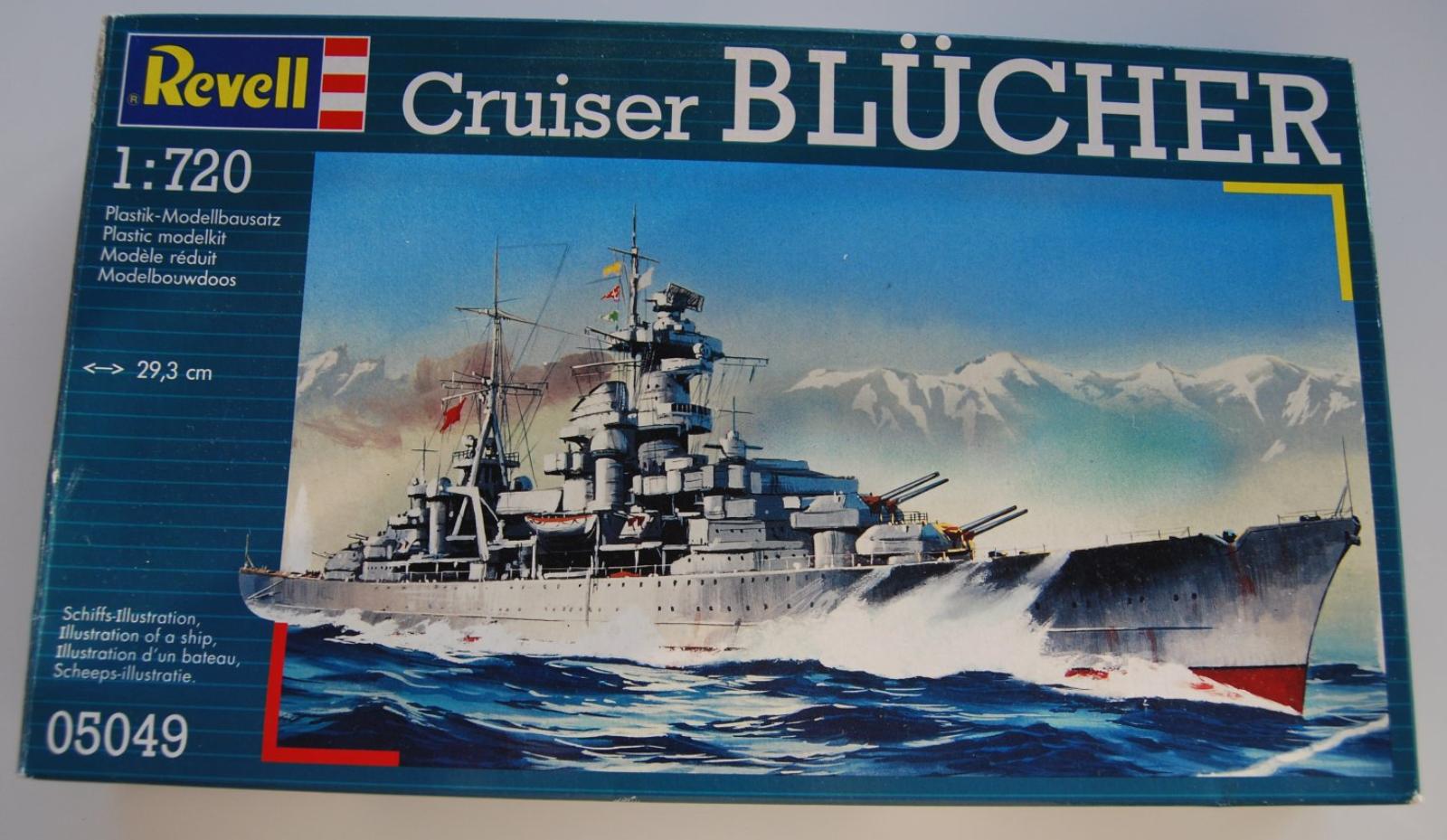

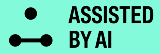

Manufacturer: Revell

Scale: 1/720

Additional parts: plastic sheets, parts from a Trumpeter Slava, PE parts

Model build: Feb - Jun 2015

Manufacturer: Revell

Scale: 1/720

Additional parts: plastic sheets, parts from a Trumpeter Slava, PE parts

Model build: Feb - Jun 2015

Captain Vasiliev surveyed the Baltic Sea from the bridge of the Petropavlovsk, the crisp April air biting at his cheeks. This wasn't your typical Soviet warship. Once a relic of a bygone era, the Petropavlovsk had been reborn as a steel testament to the future - the world's first ballistic missile cruiser. Today was the day they would unleash that future.

"Captain," came the clipped voice of First Officer Petrov, "missile bay reports they're ready for hot launch."

Vasiliev's eyes narrowed. Hot launch. It was a risky maneuver, powering up the missile on the launch pad before firing. Faster, yes, but it meant praying the temperamental R-11 wouldn't cook off prematurely. "Very well. Prepare for launch sequence."

A nervous hum filled the bridge as the crew went through the motions with practiced precision. Below decks, technicians in grease-stained overalls monitored dials and flicked switches, their faces grim under the harsh fluorescent lights.

On the aft deck, the monstrous missile cradle dominated the scene. The R-11, a spindly silver giant, looked more like a science fiction prop than a weapon of war. A plume of white smoke erupted as the first stage ignited, roaring to life with a deafening scream. The entire ship shuddered under the strain.

Vasiliev gripped the bridge railing, his knuckles white. Seconds crawled by, each one an eternity. Then, with a fiery burst, the R-11 shot upwards, leaving a trail of black smoke in its wake. The crew erupted in cheers, the tension finally broken.

But Vasiliev felt a knot of unease tighten in his gut. The cheers died down as quickly as they started, replaced by an anxious silence. The designated target, an uninhabited island hundreds of kilometers away, remained frustratingly still on the radar screen.

Minutes ticked by. Still nothing. Had the missile malfunctioned? Detonated prematurely?

Suddenly, a flicker on the screen. A growing blip. Then, a triumphant roar from communications. "Target acquired, Captain! Direct hit!"

Relief washed over Vasiliev, warm and welcome. The Petropavlovsk had done it. It had become the first ship to successfully launch a ballistic missile. This was a game-changer, a Soviet fist shaking in the face of the West.

But as the celebrations began, a chilling thought crossed Vasiliev's mind. This power, this destructive force, was now in their hands. The future, once bright with promise, suddenly seemed a little more terrifying. The Petropavlovsk, a relic reborn, was a harbinger of a new age, an age where the sea could rain down fire from the sky. And Vasiliev, its captain, stood at the precipice of that age, both exhilarated and deeply afraid.

The story of the Soviet cruiser Petropavlovsk is one of the strangest in naval history — a German heavy cruiser sold half-finished, battered in the defense of Leningrad, raised twice from the seabed… and, in this alternate timeline, reborn as one of the world’s first ballistic-missile surface combatants.

When Germany sold the incomplete heavy cruiser Lützow to the Soviet Union in 1940, the ship was only 70% finished. Renamed Petropavlovsk, she arrived in Leningrad with only her “A” and “D” 20.3 cm turrets installed, rudimentary superstructures, and unfinished machinery.

Despite her incomplete state, the Soviets pressed the ship into service as a floating battery when the Wehrmacht approached Leningrad in 1941. Firing hundreds of shells and enduring over fifty 210 mm hits, Petropavlovsk eventually sank in shallow water, only to be raised, patched, and used again before the war’s end.

Plans to complete her postwar as a light cruiser were abandoned — but the hull remained, quietly rusting in Leningrad’s backwaters throughout the early Cold War.

By 1955, as the USSR rapidly advanced its ballistic-missile program, naval designers confronted a dangerous possibility:

What if submarine-based missile systems failed?

As a safeguard, the Soviet Navy decided to convert an existing hull into a surface-launched ballistic-missile ship — a testbed and stopgap platform.

The forgotten Petropavlovsk, solidly built and conveniently available, was selected for the experiment.

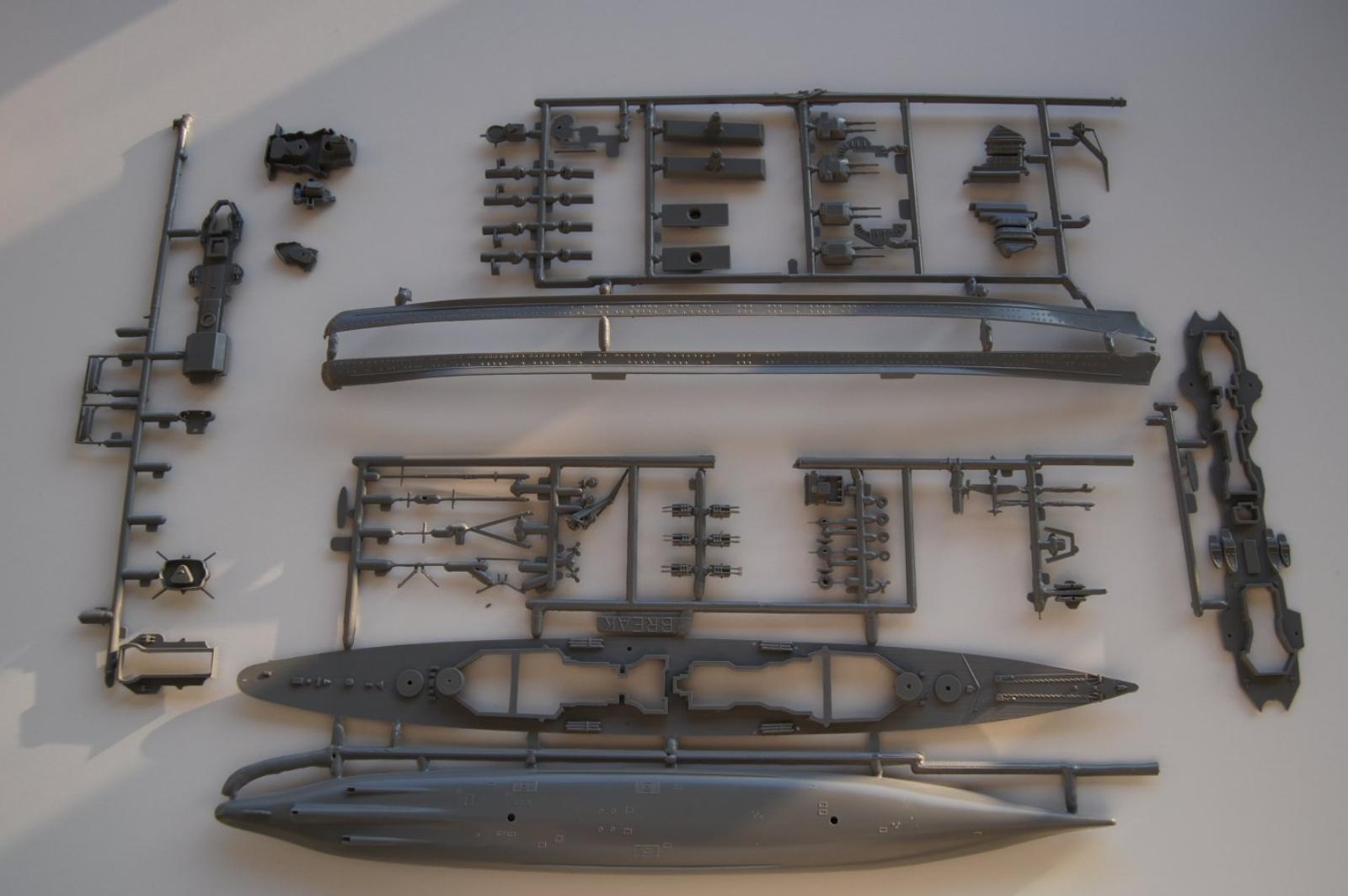

The conversion was radical:

Both stern 20.3 cm turrets were removed.

A massive missile hangar and launch complex was constructed aft.

Space for 12 R-11 ballistic missiles (an early ancestor of the Scud) was built into the new superstructure.

A helicopter deck and a small hangar were added for observation and targeting support.

Turret “D” was moved forward into the former “B” position, giving the ship four heavy guns forward.

Internally, the ship was rewired and re-engined, though much of the original German steel remained. After nearly two decades of dormancy, the cruiser was alive again.

On 4 September 1957, Petropavlovsk was recommissioned into the Baltic Fleet as the world’s first operational ballistic-missile surface combatant.

The first missile launch occurred seven months later — a successful firing of an R-11 ballistic missile into the Barents Sea. While impressive, the trials made one truth painfully clear:

A ballistic-missile ship was far too vulnerable in the era of jet aircraft and modern submarines.

Submarines quickly proved superior platforms. Nevertheless, Petropavlovsk remained valuable as a testbed, gradually becoming a floating laboratory for nearly every Soviet naval weapons system of the 1960s and early 1970s.

Over the years, her profile changed drastically:

The original German 20.3 cm guns were removed.

Replaced first by AK-726, then by AK-100 dual-purpose gun mounts.

A growing forest of AK-630 CIWS turrets bristled on her decks.

Several early SAM systems were tested aboard her.

Later, even second-generation ballistic-missile prototypes were fired from her modified launch cells.

To NATO intelligence officers, the old cruiser became a ghost — appearing with a different silhouette almost every year.

By 1976, after nearly 35 years of intermittent service, the aging hull could no longer support further testing.

Petropavlovsk was decommissioned and stripped of armament.

Rather than scrap her outright, the Navy towed the hull north, using it as a floating storage vessel until the end of the Soviet era.

In the mid-1990s, the rust-scarred former cruiser — once German, twice sunk, and reborn as a Cold War missile fortress — was quietly towed to Murmansk, where she remains today, a forgotten relic moored in the shadow of the Kola Peninsula’s nuclear dockyards.

If submarines had failed, Petropavlovsk might have become the prototype for a new generation of missile cruisers — surface-based guarantors of Soviet strategic deterrence. Instead, she became a technological stepping stone, contributing silently to early Soviet missile development.

In this alternate history, Petropavlovsk stands as one of the most improbable warships ever to sail:

born German, baptized in the Siege of Leningrad, resurrected as a Cold War missile carrier, and surviving decades longer than any sister ship that never was.

The model shows the ship in its final state in June 1975.

The model is based on the Revell 1/720 Blücher kit. Whis is a pretty simple and not-so-detailed one. The hangar structure was made from plastic sheets. The Russian/Soviet weapons and sensors were taken from a 1/700 Trumpeter Slava and a Dragon Sovremenny. The modell is airbrushed with Revell Aqua colors. Some Eduard PE Crew members were added.