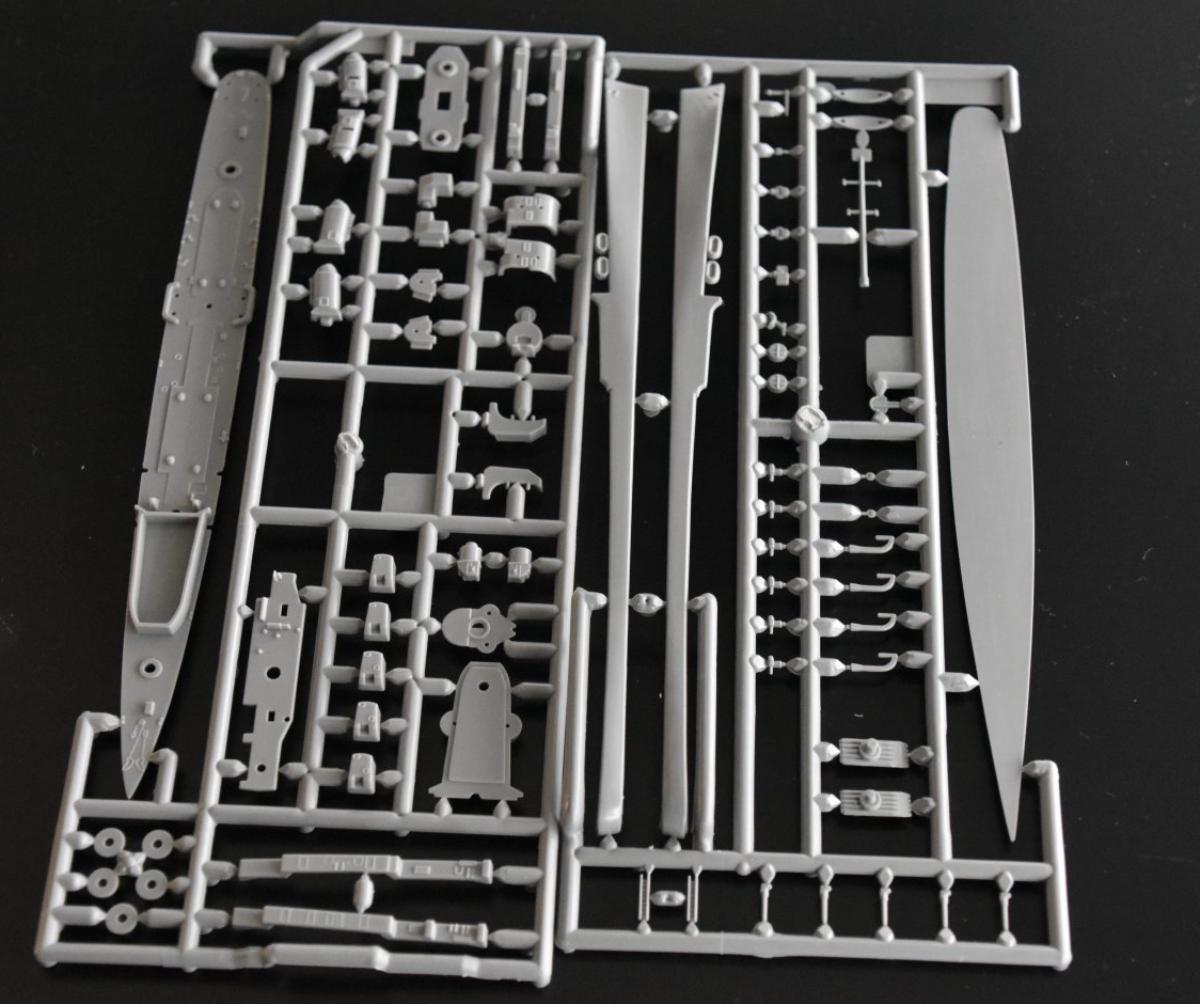

Manufacturer: Matchbox

Scale: 1/700

Additional parts: parts from spare part box, 3D prints

Model build: Feb - Mar 2021

Manufacturer: Matchbox

Scale: 1/700

Additional parts: parts from spare part box, 3D prints

Model build: Feb - Mar 2021

The icy wind whipped across the North Atlantic, biting through Lieutenant Commander Jean Dubois’ uniform as he stood on the bridge of the Jules Verne. March 1961, and the retrofitted destroyer, once a hunter, was now a guardian - a guardian angel for submarines in distress. Its mission: rescue the crew of the Norwegian submarine Kaura, trapped 180 meters below the surface.

The Jules Verne, no longer bristling with guns, had a different kind of firepower now. Its heart was the miniature submarine nestled on the aft deck - the Nemo. A marvel of French engineering, the Nemo, named after Verne’s fictional Captain Nemo, could carry 20 souls and dive to a thousand meters. Today, its mission was desperate. The Kaura had suffered a malfunction during a routine patrol, and time was running out for its crew.

Dubois, a veteran of the Algerian War, felt a knot of tension in his gut. This was their first real test, the first time the Jules Verne and Nemo would be thrown into the unforgiving embrace of the deep. Below, crews scurried around the Nemo, making final preparations. Ensign Laurent, the pilot, a man barely out of his twenties, climbed into the cramped cockpit, his face grim with determination.

The deployment was a well-rehearsed ballet. The crane hoisted the Nemo into the churning sea. Laurent’s voice crackled through the comms, calm amidst the growing storm. “Nemo ready to dive, Jules Verne.”

“Nemo, commence dive,” came Dubois’ reply, his voice tight.

The tiny submarine plunged into the inky abyss. The world inside the Jules Verne became a tense vigil. Sonar pings echoed in the control room, the only sound breaking the stifling silence. Every ping felt like an eternity.

Then, a crackle. “Jules Verne, this is Nemo. Visual contact with Kaura. Hull breach detected on forward section.”

A cold dread filled Dubois. A hull breach meant a compromised atmosphere. The urgency doubled.

“Nemo, prepare for docking.”

The docking procedure was delicate. Laurent maneuvered the Nemo with the precision of a surgeon, finally latching onto the Kaura’s escape hatch. Time seemed to distort as Laurent reported system failures on the Nemo. They were running low on oxygen.

Dubois made a split-second decision. “Nemo, emergency evacuation. Transfer maximum personnel per dive.”

The next few hours were a blur of frantic activity. Three harrowing dives ferried most of the Kaura’s crew to safety. But with each dive, the Nemo’s vitals worsened.

Finally, only the Captain and two crewmen remained on the Kaura. Hope dwindled with the Nemo’s oxygen reserves. Then, a miracle. A frantic message from the Kaura. They had managed to jury-rig their own systems and were attempting a surface ascent.

Relief washed over Dubois like a wave. On the surface, the battered Kaura emerged, its crew weak but alive. Cheers erupted on the Jules Verne’s deck, a stark contrast to the tense silence of the past few hours.

The Jules Verne had tasted its first success, a baptism by fire in the icy depths. As they sailed back, the setting sun cast a long golden glow across the sea, a silent testament to the courage of men and the marvel of machines that defied the ocean’s wrath.

An alternative-history naval chronicle

When France entered the 1950s, its fleet was undergoing a rapid transformation fueled by the Mutual Defence Assistance Act. The acquisition of the US aircraft carriers La Fayette and Bois Belleau marked a turning point for the Marine Nationale. Alongside these ships came four surplus American Fletcher-class destroyers, vessels the French Navy had little immediate need for.

Yet, as the Cold War intensified and the world’s submarines grew faster, deeper-diving, and far more complex, an unexpected requirement emerged: France lacked any means to rescue the crew of a sunken submarine. The memory of wartime undersea losses, still fresh in the minds of naval planners, pushed the idea of a dedicated deep-sea rescue craft to the forefront.

By 1953, French engineers had begun sketching the first concepts of a véhicule de sauvetage en haute mer—the VSM—a radical submersible intended to lock onto a sunken submarine’s escape hatch and evacuate its crew. The United States had not yet built its DSRV, and France hoped to pioneer the technology.

A high-speed transport platform was required to deploy the VSM anywhere in the North Atlantic within days. Among the idle Fletcher destroyers, one ship stood out: the former USS Fullam (DD-474), still in relatively good condition. Rather than scrap her, the French decided to transform her into an entirely new kind of vessel—a navire de sauvetage sous-marin, a deep-sea rescue mother ship.

Between 1955 and 1958, the Fullam underwent a radical metamorphosis at Brest.

The forward superstructure and guns were retained for defense.

The entire aft section was stripped down to the deck.

A heavy-lift rescue crane was installed.

Torpedo tubes were removed to make space for small support craft and decompression systems.

A specialized launch cradle for the new submersible was built directly into the stern.

Rechristened DDRS-01 Jules Verne, the ship honored France’s visionary author of underwater adventure.

The VSM submersible, now officially named Nemo, was completed in 1961 after years of engineering setbacks. Capable of carrying 20 survivors and diving to 1,000 meters, it was one of the most advanced rescue vehicles of its era.

For nearly three decades, the Jules Verne and Nemo formed the backbone of France’s submarine rescue capability. Their duties included:

major NATO rescue drills in the North Atlantic

joint operations with Britain, Norway, the Netherlands, and the United States

regular Mediterranean training flights between Toulon, Naples, and Malta

The Jules Verne was not a glamorous ship, but within naval circles it became legendary—an unassuming destroyer rebuilt for a noble and lifesaving mission.

The Nemo’s moment of truth came sooner than anyone expected. On 14 December 1961, the Norwegian submarine Kaura suffered a catastrophic diving accident off Bodø and settled on the seabed at 180 meters, too deep for conventional escape, but within the reach of the VSM.

The Jules Verne, already participating in a NATO exercise, reached the site within 14 hours. In three tense rescue dives:

Most of Kaura’s crew were evacuated and brought to the surface.

The remaining crew managed to restart key systems and eventually blow ballast to rise safely.

This operation cemented the international reputation of the French rescue program, even though it would never again be called upon in a real emergency.

By the late 1980s, newer technologies—mini-submersibles, deep-diving ROVs, and NATO-wide rescue systems, made the aging Jules Verne obsolete. In 1989, after 28 years of service, both Jules Verne and Nemo were formally retired.

Although never famous, they represented a remarkable chapter in naval engineering—when an aging American destroyer and a French experimental submersible quietly pioneered a capability most major navies would not fully develop until decades later.

Today, both vessels are forgotten by the public—but within naval history circles, the Jules Verne and Nemo remain early icons of Cold War submarine rescue operations.

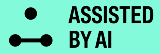

The model is based on a 1/700 scale Matchbox Fletcher kit. The VSM and the transport rack are 3D printed with a SLA printer, additional boats, cranes and other parts were taken from the spare part box. PE parts are from Eduard. The model is painted in Revell Aqua Color.

3D models used: DSRV by RRWerft (Thingiverse)